Tuesday, January 31, 2006

Clinton: Climate change is the world's biggest worry

By DAN PERRY

Associated Press Writer

January 28, 2006, 2:00 PM EST

DAVOS, Switzerland -- Former U.S. President Bill Clinton told corporate chieftains and political bigwigs Saturday that climate change was the world's biggest problem _ followed by global inequality and the "apparently irreconcilable" religious and cultural differences behind terrorism.

Clinton's comments provided something a freewheeling and philosophical finale _ ahead of Sunday's formal wrap-up _ to several days of high-powered discourse on the state of the world, and the mostly admiring audience seemed to hang on his every word.

"First, I worry about climate change," Clinton said in an onstage conversation with the founder of the World Economic Forum. "It's the only thing that I believe has the power to fundamentally end the march of civilization as we know it, and make a lot of the other efforts that we're making irrelevant and impossible."

Clinton called for "a serious global effort to develop a clean energy future" to avoid the onset of another ice age.

He also said the current global system "works to aggravate rather than ameliorate inequality" between and within nations _ including in the United States, where he lamented the "growing concentration of wealth at the top," alongside stagnation for the middle classes and rising poverty.

"I don't think we've found the way to promote economic and political integration in a manner that benefits the vast majority of the people in all societies and makes them feel that they are benefited by it," he said. "Voters usually see ... issues from the prism of their own experience."

Clinton won frequent enthusiastic applause _ not a common situation at the annual gathering in the Swiss Alps _ for articulating a global vision more conciliatory and inclusive than the one many of the assembled tend to associate with U.S. politics.

People around the world "basically want to know that we're on their side, that we wish them well, that we want the best for them, that we're pulling for them," he said.

Clinton called on current world leaders to seek ways of easing the "apparently irreconcilable religious and cultural differences in the world, that are manifest most stunningly in headlines about terrorist actions but really go far beyond that."

"You really can't have a global economy or a global society or a global approach to health and other things unless there is some sense of global community."

Former Australian foreign minister Gareth Evans was listening. "He's a great performer and then he's got the greatest convening power of anyone now in the world, I think, and the greatest capacity to articulate things that matter," said Evans, who now heads the International Crisis Group, a think tank.

Clinton also dispensed advice on the issues of the day.

In Iraq, he said, the United States should not "give this thing up and say it can't work," but should consider "drawing down some of our troops and reconfiguring their components, trying to increase the special forces (and) putting them in places where they're not quite as vulnerable."

Iran, he argued, must not be allowed to acquire nuclear weapons, and neither economic sanctions nor "any other option" should be ruled out as ways of preventing this. But he warned there would be "an enormous political price to pay if the global community ... looked like they went to force before everything else has been exhausted."

Clinton also suggested the West should be more open to eventual dialogue with Hamas, the radical Palestinian group whose election victory stunned the world this week and clouded the prospects of any resolution to the conflict with Israel.

"One of the politically correct things in American politics ... is we just don't talk to some people that we don't like, particularly if they ever killed anybody in a way that we hate," he said. "I do think that if you've got enough self-confidence in who you are and what you believe in, you ought not to be scared to talk to anybody."

"You've got to find a way to at least open doors ... and I don't see how we can do it without more contact," he said. Hamas might "acquire a greater sense of responsibility, and as they do we have to be willing to act on that."

Klaus Schwab, the forum's founder and organizer, asked Clinton to advise the next U.S. president, noting that this person might either be married to Clinton or listening in the audience _ an apparent reference to Sen. John McCain, seated in the first row along with Microsoft's Bill Gates and other invitees.

"In this world full of culturally charged issues I think we should make it clear that Senator McCain and I are not married," Clinton joked as the audience burst into laughter.

The comment earned Clinton a slap on the back from the Arizona Republican, who fought a crowd to get to the former president after the event.

"Interesting talk," said the beaming possible 2008 presidential contender. "You got us both in trouble!"

Monday, January 23, 2006

Be Open to Possibilities

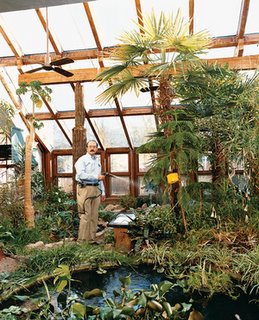

AMORY LOVINS is a physicist, economist, inventor, automobile designer, consultant to 18 heads of state, author of 29 books, and cofounder of Rocky Mountain Institute, an environmental think tank. most of all, he's a man who takes pride in saving energy. The electricity bill at his 4,000-square-foot home in Old Snowmass, Colorado, is five dollars a month, and he's convinced he can do the same for all of us. His book "Winning the Oil Endgame" shows how the united states can save as much oil as it gets from the persian gulf by 2015 and how all oil imports can be eliminated by 2040. And that's just for starters.

(Right:Lovins waters tropical plants in a hothouse that serves as a "furnace" for his home/office in Old Snowmass, Colorado, where subfreezing temperatures are common throughout the winter. Overhead windows have special coatings that let light through but reflect interior heat. The pond is home to catfish, frogs, and crayfish.)

By Cal Fussman Photography by Ben Stechschulte

DISCOVER Vol. 27 No. 02

When I give talks about energy, the audience already knows about the problems. That's not what they've come to hear. So I don't talk about problems, only solutions. But after a while, during the question period, someone in the back will get up and give a long riff about all the bad things that are happening—most of which are basically true. There's only one way I've found to deal with that. After this person calms down, I gently ask whether feeling that way makes him more effective.As René Dubos, the famous biologist, once said, "Despair is a sin."

ENERGY

I used to work for Edwin Land, the father of Polaroid photography. Land said that invention was the sudden cessation of stupidity. He also said that people who seem to have had a new idea often have just stopped having an old idea. So I suppose if I bring something unusual to this business, it's that maybe I find it easier to stop having old ideas.

I can't point to any one moment in particular from my past that made me who I am. It's been more like seeing the world through an evolving lens. Gradually, I've learned to ask different questions and look at problems from different angles than most people. I'm probably best known for having redefined the energy problem in 1976 with a Foreign Affairs article titled "Energy Strategy: The Road Not Taken?"Until then, the energy problem was generally considered to be: Where do we get more energy? People were preoccupied with where we could get more energy of any kind, from any sources, for any price—as if all our needs were the same. I started instead at the other end of the problem: What do we want the energy for?

You don't generally want lumps of coal or barrels of sticky black goo. You want comfort, illumination, mobility, baked bread, and so on. And for each of these end uses we should ask: How much energy, of what quality, at what scale, from what source will do the job in the cheapest way? That's now called the end-use/least-cost approach, and a lot of the work we do at Rocky Mountain Institute involves applying it to a wide range of situations. End-use/least-cost analysis begins with a simple question: What are you really trying to do? If you go to the hardware store looking for a drill, chances are what you really want is not a drill but a hole. And then there's a reason you want the hole. If you ask enough layers of "Why?"—as Taiichi Ohno, the inventor of the Toyota production system, told us—you typically get to the root of the problem.

OIL

Let's start with one basic problem. Saudi Arabia has a quarter of the world's oil reserves. It is the sole swing producer with significant capacity to increase output, and therefore it controls the world price. Two-thirds of Saudi oil flows through one processing plant and two terminals that are in the crosshairs of terrorists. That stuff could go down any day for a long time. And that would presumably crash both the House of Saud and the Western economy. So for the bad guys it's a twofer. They would love to do that, and they've already had a couple of cracks at it. Now, this should make you uncomfortable. But we don't have to continue on our current path. We can go a different way.

Let's look at oil through a historic analogy. Around 1850, the biggest or second-biggest industry in America was whaling. Most buildings were lit with whale oil. But in the nine years before Edwin Drake struck oil in 1859 in Pennsylvania and made kerosene ubiquitous, at least five-sixths of the whale oil–lighting market had already been lost to competing products made from coal. This was elicited by the relatively high price of whale oil as the whales got shy and scarce.

The whalers were astounded that they ran out of customers before they ran out of whales. They didn't see this coming because they hadn't added up the competitors. Oil fields can be like this today. The United States today wrings twice as much work from each barrel of oil as it did in 1975. With even more advanced technologies, we can double oil efficiency all over again at a cost averaging $12 a barrel. We can replace the rest of our oil needs with advanced biofuels and saved natural gas at a cost averaging $18 a barrel. Combined, these two approaches average out at a cost of $15 a barrel. That's a lot cheaper than the $61 per barrel oil was the other day or even the $26 that's officially forecast for the year 2025. How much cheaper than $26 a barrel? Well, about $70 billion a year, plus a million jobs, mostly in rural and small-town America. Plus a million saved jobs now at risk, mainly in the automaking states.

We've got a choice: Either we're going to continue importing efficient cars to help replace foreign oil, or we're going to employ our own people to make efficient cars and import neither the oil nor the car—which sounds like a better idea.

WEIGHT

A modern car, after 120 years of devoted engineering effort since Gottlieb Daimler built the first gasoline-powered vehicle, uses less than 1 percent of its fuel to move the driver. How does that happen?Well, only an eighth of the fuel energy reaches the wheels. The rest of it is lost in the engine, drivetrain, and accessories, or wasted while the car is idling. Of the one-eighth that reaches the wheels, over half heats the tires on the road or the air that the car pushes aside. So only 6 percent of the original fuel energy accelerates the car. But remember, about 95 percent of the mass being accelerated is the car—not the driver. Hence, less than 1 percent of the fuel energy moves the driver. This is not very gratifying. Well, the solution is equally inherent in the basic physics I just described. Three-quarters of the fuel usage is caused by the car's weight. Every unit of energy you save at the wheels by making the car a lot lighter will save an additional seven units of fuel that you don't need to waste getting it to the wheels.

So you can get this roughly eightfold leverage (three- to fourfold in the case of a hybrid) from the wheels back to the fuel tank by starting with the physics of the car, making it lighter and with lower drag. And indeed you can make the car radically lighter. We've figured out a cost-effective way to do that so you can end up with a 66-mile-per-gallon uncompromised SUV that has half the normal weight, has a third the normal fuel use, is safer, and repays the extra cost that comes with being a hybrid in less than two years.

PLASTIC

(Right: An automotive seat bucket from Fiberforge, a company chaired by Lovins, is ultralight and ultrastrong. Carbon fibers are laid into predetermined positions and sandwiched with reinforcing nylon. The flat, tailored blank is then heated, stamped on a hot molding die, cooled, and trimmed to produce the finished part.)

Henry Ford said you don't need weight for strength. If you did need weight for strength, your bicycle helmet would be made of steel, not carbon fiber. And if you want to know how strong a very light material can be, try eating an Atlantic lobster with no tools. The auto industry needs to move toward ultralight, ultrastrong carbon-fiber composites, almost certainly using thermoplastics that flow when heated and that can be easily molded—instead of the more brittle, expensive thermosets that need chemistry, baking, or some other change to set the resin into its final hard form. Thermoplastics are incredibly tough. They can absorb 12 times as much crash energy per pound as steel. So even though your car will be only half as heavy as it was before, it will still be safer when whacked by a heavier one.

With such materials, you can decouple size from weight. You can make the car big—protected and comfortable. But it won't be heavy—hostile and inefficient. This can save oil and lives at the same time, and it turns out you can greatly improve the economics of making the car because you might have in a carbon SUV only 14 body parts—instead of 140 to 280 in a steel auto body—each needing one low-pressure die set, instead of an average of four high-pressure steel-stamping die sets in the steel body. The parts snap together precisely in the right positions for gluing, like assembling a kid's toy, so you don't need all those jigs and robots. You basically get rid of the body shop this way, and then by laying color in the mold, you get rid of the paint shop too. There go the two hardest and costliest parts of making the car.

New jobs come partly by having a vibrantly competitive car industry rather than a failing one and partly due to the logical evolution of the auto industry toward computerization. Imagine the aftermarket for improved and customized software. The industry structure would be different, but we don't think there would be a net loss of jobs. The jobs would be safer, healthier, and better distributed. And the same revolution that's coming to automaking from advanced materials also applies to anything else that moves.

HYDROGEN

Many automakers are starting to understand that whoever goes ultralight first will take the lead in the hydrogen fuel-cell race.The winning strategy will be improving the physics of the car. They still need to make a cheap, durable fuel cell. But if they can reduce the fuel cell and the hydrogen storage volume by three times, the cost reduces threefold.

That said, superefficient cars need hydrogen a lot less than hydrogen needs superefficient cars. If you have, say, an ultralight hybrid SUV burning gasoline at 66 miles per gallon, that isn't so bad—at least not compared to a similar one getting 18.5 miles per gallon on the road today.

If you then combine that with E85 fuel, which is 15 percent gasoline and 85 percent ethanol, you just got a 320-mile-per-gallon SUV because the efficiency times the biofuel saving of oil multiplies.For that matter, if every car or light truck on the road in 2025 is only as efficient as the best hybrid cars and SUVs now in the showrooms, that would save twice as much oil as we currently import from the Persian Gulf. So it's not a very ambitious goal—and it doesn't even involve making vehicles ultralight. Very efficient vehicles can get most of the same benefits without hydrogen by using today's gasoline/hybrid propulsion. However, once you have such vehicles, there is a robust business case for running them on hydrogen. Until you have those efficient vehicles, that business case is not very convincing.

I think hydrogen will be an important if not dominant energy carrier by 2050. In Winning the Oil Endgame, the comprehensive strategy we've developed at Rocky Mountain Institute for ending oil dependence, we see hydrogen as an optional add-on. It would be the most profitable and efficient way to use and save natural gas. But it's not necessary to get the country off oil at a profit; it's just icing on the cake.

ELECTRICITY

A question I ask a lot is, What's the right size for the job? I have a book called Small Is Profitable: The Hidden Economic Benefits of Making Electrical Resources the Right Size. It points out 207 benefits of distributed resources, such as solar and wind power. When I begin to describe them, you'll find them really obvious:Renewables, such as wind energy, have less financial risk from volatile fuel prices than fossil-fuel power plants because they don't need any fuel.Small resources like solar cells or wind turbines have less financial risk than giant power plants that take many years to build. Portable resources like solar panels have less financial risk than stationary power plants, because if the system evolves differently than you'd expected and you'd rather put it somewhere else, you simply stick it on a truck and move it. This is all blindingly obvious, yet it hasn't been taken into account by the utility industry while buying its half trillion dollars' worth of assets.

Here's what happened: For the first century of the electricity business, the power plants were costlier and less reliable than the grid, so it made sense to build a bunch of big power plants backing each other up through the grid. Well—surprise—over the last 20 years, power plants have become cheaper and more reliable than the grid. Ninety-nine percent of our power failures originate in the grid—mostly in distribution. So now if you want to deliver reliable, affordable electricity, you need to make it at or near the customer's location. Many people didn't notice this happening. But despite the market's not yet recognizing the benefits, the decentralized low- or no-carbon generators turn out to be greater in capacity and output than nuclear power worldwide. David already beat Goliath, but nobody noticed. The nuclear advocates frequently state that only nuclear is big and fast enough to deal with global warming. Well, five years from now the official industry forecast suggests that decentralized low- and no-carbon generators will be adding 160 times as much capacity as nuclear will add up to that year. So those who think that the decentralized generators are small, slow, and futuristic or have an unacceptable risk of not being adopted at scale in the market have some serious explaining to do.

WIND

If I could do just one thing to solve our energy problems, I would allow energy to compete fairly at honest prices regardless of which kind it is, what technology it uses, how big it is, or who owns it. If we did that, we wouldn't have an oil problem, a climate problem, or a nuclear proliferation problem. Those are all artifacts of public policies that have distorted the market into buying things it wouldn't otherwise have bought because they were turkeys.

We have more than enough cost-effective wind power just on available land in the Dakotas to meet the United States' electricity needs. We wouldn't necessarily want to do it all in two states, and there are cheaper combinations of other technologies to do the whole job, but it's an enormous resource. Germany and Spain each install over 2,000 megawatts of wind power every year. That figure exceeds the average global net addition of nuclear power every year in this decade. Denmark is now one-fifth wind powered; Germany, about a tenth.Wind power is doubling every three years worldwide and solar power every two, and not because some countries subsidize it strongly. In fact, the subsidies are being phased out slowly in Germany and rapidly in Japan because they have achieved their purpose of creating world-class industries that will be able to make it on their own.

If everything competed solely on merit, wind energy in the United States would be a lot better off. It gets subsidized less than its competitors, and its subsidies are temporary, while its competitors' are permanent. In other words, the fossil and nuclear subsidies—nuclear being the biggest—are permanent, while renewable subsidies are temporary.Congress's brief and irregular renewals of the tax credit for wind power have several times bankrupted wind-turbine manufacturers in the United States. Similar misguided policies have diminished the solar-cell industry. Half of the solar cells sold in the United States a decade ago were domestically made. Now that figure is only 8 percent.

DEFENSE

A major player in our energy future will be the Pentagon. Here's why: Trailing behind every half-mile-a-gallon Abrams tank—a peerless fighting machine if you can get it there—are two unarmored fuel trucks. Guess what the bad guys shoot at?

This is a very teachable moment—when the Pentagon becomes acutely aware of the cost and the risk of delivering fuel on the battlefield. They obviously need much lighter, more agile, radically more fuel-efficient forces. A military transformation will have a much bigger payoff, in exactly the same way the Pentagon's research and development created the Internet, global positioning systems, the modern microchip industry, and advanced aero engines.

If you align military science and technology investments to capture this enormous improvement at a tactical, operational, and strategic level, guess what? You thereby transform the car, truck, and plane industries to get the country off oil, so we won't need to fight over the oil because we won't be using it. Mission unnecessary.

BANANAS

When we designed the research facilities at Rocky Mountain Institute, we didn't plan on having a banana farm inside. We're up 7,100 feet in the Rockies, and it has gotten as low as –47 degrees in the winter.We planned about 900 square feet of jungle space with five different kinds of energy collection: heat, hot air, hot water, light, and photosynthesis. The arch that holds it up has 12 different functions, but I paid for it only once. The whole building exemplifies design integration: getting multiple benefits from single expenditures. It saves about 99 percent of the normal need for space- and water-heating energy, about 90 percent of the household electricity, and half the water. All that efficiency paid for itself in 10 months—and that's with 1983 technology! Now we can do a lot better.

Anyway, we weren't planning on growing bananas here, but somebody who owed me something gave me a banana tree to settle the obligation. He said it would grow to six feet and never fruit—but he forgot to tell the tree. When it got 12-year-old horse manure, it went bananas, grew to 25 feet, put out nine crops in the first year and a half, and tried to go through the roof. Then it tried to eat the fishpond.

I was afraid of a hydraulic disaster, so we chopped it down, dug it up, and put a steel fence between what was left of the root-ball and the fishpond. But it grew back and put out another 18 crops. Eventually, a few years ago, it wore out at twice its designed life, so we took it out for good and put in a variety of young banana trees. We've also done mangoes, grapes, papayas, and passion fruit—here in the Rocky Mountains.

The tangled tale of the banana tree offers a very simple lesson: Be open to possibilities.

Sunday, January 15, 2006

China Now the World’s Second Largest Auto Market

China Now the World’s Second Largest Auto Market

14 January 2006

http://www.greencarcongress.com/

Statistics from the China Automotive Industry Association (CAIA) indicate that China has surpassed Japan as the second-largest auto market in the world, behind the US.

The total number of automobiles sold in the Chinese market reached more than 5.9 million in 2005, outstripping the 5.8 million of the Japanese market. Of those, 5.76 million were produced domestically, the remainder were imports.

Sales have risen dramatically from the 2.73 million units sold in 2001. As a percentage of global sales, China now represents 8.7%, up from 4.3% in 2001. Furthermore, in 2005, China accounted for 23.2% of the total global growth.

Xu Changming, director of Information Resources Department with the State Information Center, believes that the high-speed growth of the passenger vehicles last year benefited mainly from the expansion into regional markets.

In 2005, the auto sales in the secondary regional market in the provinces of Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Shandong and Guangdong were up by about 40% while the sales in the tertiary markets of Hebei, Henan, Liaoning, Sichuan, Fujian, Guanxi, Shanxi, Yunnan and Tianjin grew by 50%.

Auto sales by domestic producers increased by 40.3% in the first 11 months of last year, nearly twice the sales growth of 21.3% per cent of Sino-foreign joint ventures. Of the domestic producers, the sales of Chery autos were close to 190,000 units, ranking the sixth among the sedan makers in the country, an increase of more than 110%.

Sales of commercial vehicles declined by 0.75%, influenced, according to CAIA, by the business cycle, rising oil prices and policy factors. The CAIA expects that the auto market will maintain a 10% to 15% growth in 2006, with sales reaching between 6.4 and 6.6 million units.

The top three automakers in China are First Automotive works (FAW), Shanghai Automotive Industry Corporation and Dongfeng Motor Corporation, which sold 983,100, 917,500 and 729,000 cars in 2005 respectively.

Sales of vehicles in China from GM and its joint ventures jumped 35% in 2005 to 665,390 units. GM ended the year with an estimated market share of 11.2% in this second-largest global market.

Monday, January 02, 2006

Seeking Clean Fuel for a Nation, and a Rebirth for Small-Town Montana

Here's a way to burn coal in a clean manner; however I wonder where most of the harvestable coal is located i.e. sensitive habitat areas. Make way for Environmental Impact Reports if this solution takes flight.

By TIMOTHY EGAN

HELENA, Mont., Nov. 15 - If the vast, empty plain of eastern Montana is the Saudi Arabia of coal, then Gov. Brian Schweitzer, a prairie populist with a bolo tie and an advanced degree in soil science, may be its Lawrence.

Rarely a day goes by that he does not lash out against the "sheiks, dictators, rats and crooks" who control the world oil supply or the people he calls their political handmaidens, "the best Congress that Big Oil can buy."

Governor Schweitzer, a Democrat, has a two-fisted idea for energy independence that he carries around with him. In one fist is a shank of Montana coal, black and hard. In the other fist is a vial of nearly odorless clear liquid - a synthetic fuel that came from the coal and could run cars, jets and trucks or heat homes without contributing to global warming or setting off a major fight with environmental groups, he said.

"Smell that," Mr. Schweitzer said, thrusting his vial of fuel under the noses of interested observers here in the capital, where he works in jeans with a border collie underfoot. "You hardly smell anything. This is a clean fuel, converted from coal by a chemical process. We can produce enough of this in Montana to power every American car for decades."

Coal-to-fuel conversion, which was practiced out of necessity by pariah nations like Nazi Germany and South Africa under apartheid, has been around for more than 80 years. It is called the Fischer-Tropsch process. What is new is the technology that removes and stores the pollutants during and after the making of synthetic fuel; add to that high oil prices, which have suddenly made this form of energy alchemy feasible. The coal could be converted into gasoline or diesel, which would run cars, or into other types of fuel.

With coal reserves of about 120 billion tons, Montana has one-third of the nation's total and a tenth of the global amount. Most of it is just under the prairie grass in the depopulated ranch country of eastern Montana. Mr. Schweitzer wants to plant coal-to-fuel factories in towns that have one foot in the grave. It may not provide enough fuel to wean the West off imported oil, but it may be enough to show the rest of the country that there is another way, he said.

"This country has no energy plan, no vision for the future," said Mr. Schweitzer, who spent seven years in Saudi Arabia on irrigation projects. "We give more tax breaks and money for oil, and what do we get? Three-dollar gas and wars in the Middle East. If you want to control the destiny of this country, it's going to be with synthetic fuels."

For now, the governor's ideas are just speculative. Although several energy companies have expressed interest in building coal-to-fuel plants, no sites have been chosen or projects announced. Because it would be such a novel, financially risky undertaking, companies have been hesitant to go the next step. But Mr. Schweitzer hopes for a breakthrough, with several plants up and running within 10 years, and he says he does not need legislative approval to give the go-ahead if companies commit.

The governor has met with the president of Shell Oil, the chairman of General Electric and other captains of big energy, as well as with smaller companies that develop synthetic fuels.

"This is not a pipe dream," said Jack Holmes, the president and chief executive of Syntroleum, an Oklahoma company that has a small synthetic fuels plant and wants to build something bigger. "What's exciting about this process is you don't have to drill any wells and you don't have to build any infrastructure, and you'd be putting these plants in the heartland of America, where you really need the jobs."

Certainly jobs are a big motivating factor. Montana is a poor state and ranks last in average wages. Mr. Schweitzer, whose approval rating is near 70 percent, says thousands of good-wage jobs can be gained in towns that are dying.

He is also promoting wind energy and the use of biofuels, using oil from crops like soybeans as a blend. The governor signed a measure this year that requires Montana to get 10 percent of its energy from wind power by 2010, a goal he said would be reached within a few years. Still, the Big Sky State, with a population under a million, has fewer people than the average metro area of a midsize American city, and its influence is limited. The governor acknowledged as much.

"I'm just a soil scientist trying to get people in Washington, D.C., to take the cotton out of their ears," Mr. Schweitzer said with somewhat practiced modesty. "But if we can change the world in Montana, why not try it?"

By some estimates, the United States has enough coal to take care of its energy needs for 800 years. The new, cleaner technology stores the pollutants in the ground or processes them for other uses.

The United States imports about 13 million barrels of oil a day. To replace that oil would be a monumental undertaking, with hundreds of coal-to-fuel plants. But Mr. Schweitzer points to South Africa, where a single 50-year-old plant provides 28 percent of the nation's supplies of diesel, petrol and kerosene. But the South African plant uses old technology that does not remove the pollutants.

In this country there is a small factory in North Dakota that converts coal to natural gas. And Pennsylvania is moving forward on a plan to produce diesel from coal. Neither of these plants would come close to the scale of the plants Mr. Schweitzer is envisioning in Montana, where it would cost upward of $7 billion to build a plant that could turn out 150,000 barrels of synthetic fuel a day, for about $35 a barrel.

One surprising thing, thus far, is that many people in the environmental community have not rejected the coal-to-fuel idea out of hand. Environmentalists like the process for producing clean fuels from coal. They say the technology is there and it can be done in coal-rich empty quarters of eastern Montana, North Dakota or Wyoming.

Still, they worry about strip mining the ranch country and about whether there will be a global commitment to make synthetic fuels the clean way rather than in a dirtier way along the lines of a plan in China, where the government has joined with major global oil companies to build about a dozen coal-to-fuel plants.

"It's a very interesting moment in energy history," said Ralph Cavanagh, an energy policy expert at the Natural Resources Defense Council, one of the nation's most powerful environmental groups. "Certainly this process can be done. This is a promising direction. The question is, Are we going to do it clean?"

Because there is no federal mandate to process coal in a way that reduces the emissions that can cause global warming, Mr. Cavanagh says he fears that any new coal operations will simply add new pollutants to the atmosphere. Coal plants without the cleaning technology are the biggest source of man-made carbon dioxide, a gas that is considered a central contributor to the warming of the earth, according to many studies.

There is another problem as well. Some Montana ranchers and environmentalists who fought big coal-mining proposals in the 1970's are worried about what new mining will do to the grasslands.

"The governor's idea is a big one," said Helen Waller, a farmer who is active with the Northern Plains Resource Council, a Montana environmental group. "I'm not sure it's the best one. I don't think there's any such thing as clean coal. And even if there were, it would require a lot of productive ranchland to be ripped up."

Mr. Schweitzer said the mining could be done in a way that restored the land afterward. "I call it deep farming," he said. "You take away the top eight inches of soil, remove the seam of coal, and then put the topsoil back in."

But given Montana's history of abuse by mining companies - the giant open-pit mine in Butte is the most visible legacy of a bygone era - some Montanans remain skeptical.

"I just think there's a better way that doesn't involve tearing up productive ranchland," Ms. Waller said.